When artist Edvard Munch wrote, “Sickness, madness, and death were the black angels that guarded my crib”, he was articulating the true essence of his works, characterised by evidence of anguish and despair to reflect on the reality of his mental state.

With World Mental Health Day not having gotten too far, there is little about mental health to say than what has already been said. However, what lies beyond the effort is a response of awareness and acknowledgement. Art has, on several levels, not only been a means of expression, but also supported mental health with its creative manners.

It is now time to bust some common myths about mental health that remain relevant in the present day – to realise more than to know.

Myth 1: Having a mental illness means you are “crazy”

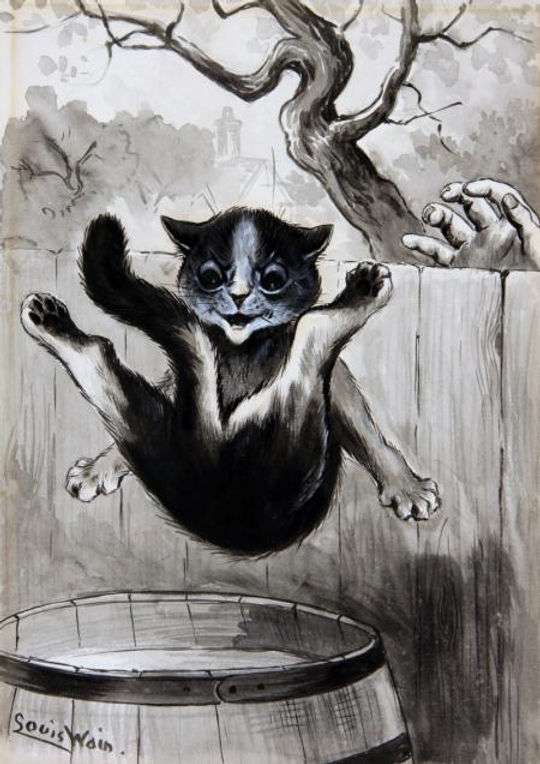

In the 19th century, artist Louis Wain was discovered with drawn attention to anthropomorphised cats. While some deemed his works erratic, his perception of the feline was recognised by the arts and led him to fame.

Apart from the several storms in his life and relationships, Wain’s mental illness was subjected to several assumptions and his behaviour, which was deemed violent and intolerable by his sisters.

While Wain’s mental condition is a subject of recurrent debate – majorly between schizophrenia, Asperger’s syndrome and visual agnosia, his primary dedication to art remained constant throughout his life. Nature was secondary in his works, which contained a strong hold of cats in different appearances.

His works were evidence to his gifted visual styles, which, in chronological order, seemed to express limitedly, but later went on to occupy roots of abstract and cubist art. A vibrancy and detail was always present in his world of cats, which explored fantastic possibilities. His works were not as much a portrayal of cats as much as a growth of their character – from silent creatures to those of exaggerated presence on regular canvases and postcards known for his illustration on them. Over time, the larger image of cats translated into intricate, yet unmissed details that appeared in psychological experimentation and understanding.

Even after being institutionalised, Wain was a subject of great detail in the arts as well as the evolving field of psychology, where his works deciphered the state of his mind, conveyed in the form of undisputed creativity, eventually hinting deterioration due to their abstract nature.

Myth 2: It should be hardly noticeable

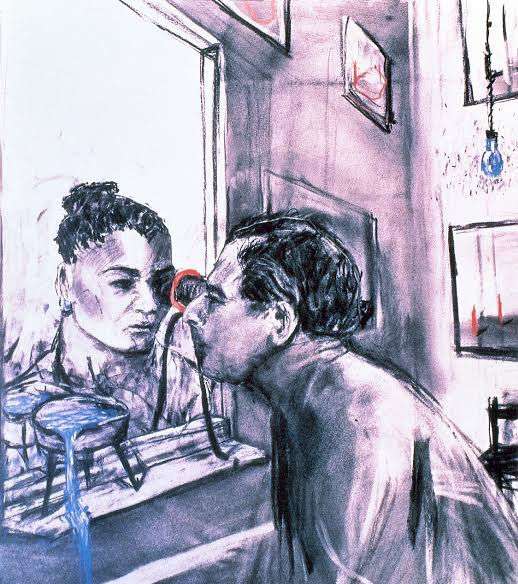

Fine-art photographer John William Keedy captures the strongest notions of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and anxiety in his project, “It’s Hardly Noticeable”, with thorough imperfection.

Each image is a consonant to the vowels of mental health: it not only addresses the condition but also how the perception of one’s life takes up the urge of maintaining order in every way possible. Together, the photographs combine to form an imagery of the mind at its best and worst.

The representation of objects found in a present routine environment is overpowered by dis-order and the plunge it takes within one’s vision. From arranging everything in a certain order to mending with residues, it takes notice of the details that would otherwise be born out of “laziness” and “irresponsibility”. The subjects in most images are accompanied by metaphors that can only be understood visually. While the photographs themselves seem imperfect, they represent attempts to achieve perfection, almost unrealistically. There is also an undercurrent of defiance that, although appealing to the eye, meets it after a long duration. A balance between satisfaction and discomfort is spread across the photographs, as they challenge how mental illness could be identified as just another habit.

The silence in Keedy’s works are filled by sounds that vary with each spectator, fitting their definition of mental health and the pace with which it occurs in their thoughts.

Myth 3: Mental illness is rare and dramatic

Artist Janelia Mould conceptualises the struggle of depression with absent presences in one’s thoughts and actions. A surreal portrait of the condition not only excuses the romanticism of a troubled mind, but also clarifies its prevalence in the society.

One of her projects, “Melancholy – a girl called depression”, is a series of undefined and scattered experiences of individuals who go through depression while trying to participate and interact with their surroundings and pretending to be “okay”. While melancholy settles down with their usual feelings, depression gradually crawls into their stasis, giving way to what has to be and what is.

With tired eyes and tired minds comes the tendency of lacking in spirit and the motivation to move even a step forward. Mould’s haunting depictions combat the romantic notions associated with mental illness and its role within the role of an individual.

From one moment to another comes an obstacle of responding to something that left their attention long ago, and only appears as a mist in the vicinity. Through the objects that replace a body, the battle put up collects strength and the willingness to fight without tracing causes or commands. Her photographs choose organic shades and the significance of remaining natural to defy the command of decorating and adjusting to societal prompts.

What stands apart the most in the series is an indication of the isolated and the misunderstood who rest their case in the bubble of mental health and emerge victorious.

Myth 4: The stigma attached to mental health is greater than itself

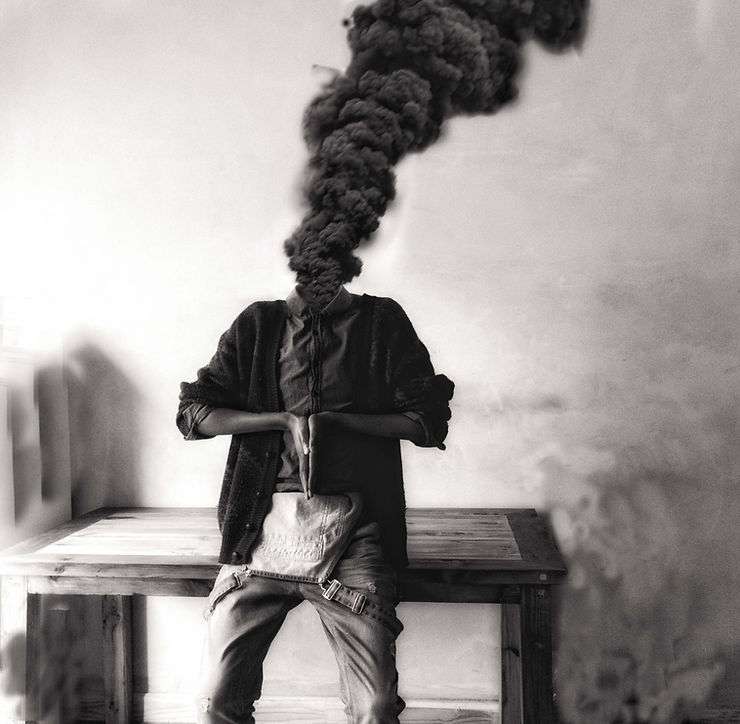

Several sketches of mental health in the Black community by South African artist Tsoku Maela find place in his visual diary, “Abstract Peaces”. Depression and anxiety are identified with direct sensory exchange, in order to hold the light of awareness. The lives of those suffering from either of the conditions is blended within the confines of commonality and support.

With the narrative of people being held hostage by mental illness, Maela brings forth the harsh and pleasant reality that navigates them through the uncertainties in life. Sentences of hope interrupt the darkness, as visuals take note of a colourless storm, waiting to be painted by the fight.

Faces are replaced by occurrences and inactivity dictates a body that is no longer a part of the whole – a notion thoroughly refuted by Maela, with the aim to bring change to perspective and the taboo that enters before the condition does. The functioning of an individual suffering from a mental illness is portrayed through partial efficiency, with the other half seeking help without hesitation.

Shot in closed spaces that refract its importance, the series contains chaotic situations and the numbness that runs in the body of the affected – especially when they cannot realise the sensation that follows.

Myth 5: Your mental illness defines you

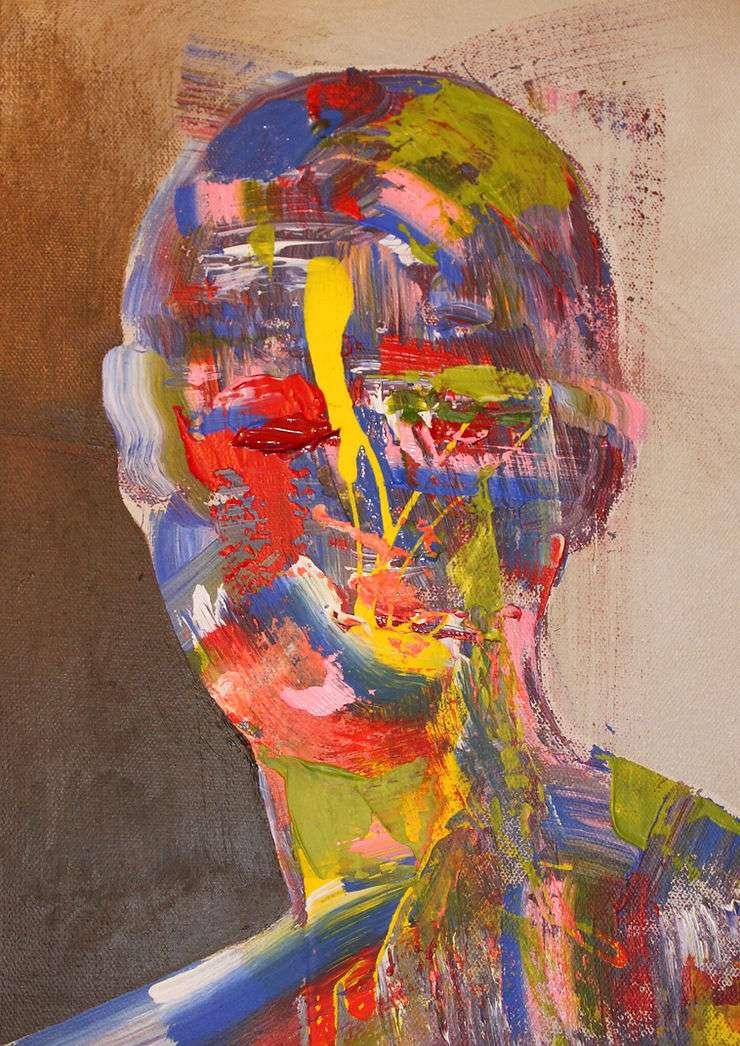

The dissociation of identity from mental illness while embracing it as a part of one’s growth comes with artists and siblings Charlie and Eddie Proudfoot. While keeping their identity under cover, they have carefully delivered the message of how one’s mental health is something to be embraced and nurtured, irrespective of where they come from, who they are and what they look like.

By leaving no trace of the face of their subjects, their paintings have bodies that seek the spirit of what awaits them in belongingness. The Proudfoots leave no leaf unturned when it comes to connecting defaced bodies with minds that cultivate their uniqueness. Bright shades decline the interaction between appearance and capabilities, further abandoned by a clear imagination of the remaining body. The portraits, arresting their thoughts in a colourful view, are made of several sources of inspiration and emotion.

The destruction of individuality in their works are a step towards addressing mental health as an important part of a larger community and not behind the closed doors that prevail.

Artists have, time and again, found visual language to be an instrument that considers the necessity of mental health globally. Whether it is a momentary connection between the artist and the spectator or relevance of works of art across time and space, mental health has taken up an important position in the arts.

In the form of a subject, it gives an in-depth image of the artist’s own psyche or how they perceive that of others. In the form of a theme, it has amplified the need to consider mental health, while also disconnecting it from identity.

Either way, it is art that has confronted the wellbeing as well as the troubles of the mind, as it has sided with mental health in the form of a therapy that captures memories and leads to a better tomorrow.

Now that you’ve come this far, find comfort through works of art here!