While walking through galleries and museums observing paintings, we can instantly connect to so many factors about what life must be like in the time of the artist and so much of the information is given to us through the portrayal of fabrics and fashion. Clothing can help us greatly to distinguish between the social classes and roles that are visible in art, making it easy to tell a pauper from a king and an heiress from a lady of the night.

To understand it best we need to take a look at what ‘Cultural Capital’ stands for. It was first coined by the French theorist Pierre Bourdieu. He refers to the perceived position of a person in a society based on various materialistic and cognitive factors. This points to the differentiation that we make between people based on materialistic and other inherited qualities. To put it simply, Cultural Capital refers to the social assets that people possess, like education, style of speech, mannerisms and also style of dressing that helps in social mobility.

In fact, it takes effort to prevent ourselves from making snap judgements about everyone we meet based on what they are wearing, their language capabilities and materialistic possessions. We know the value of labels such as Gucci, Chanel or Prada and the ‘Cultural Capital’ that is associated with these labels and products.

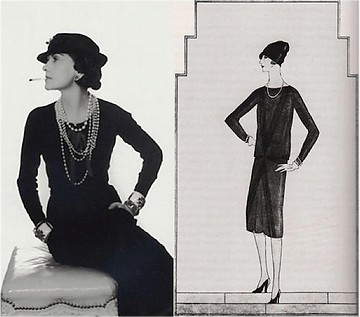

The Evolution of the Little Black Dress

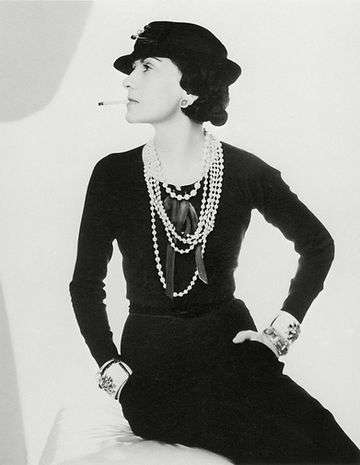

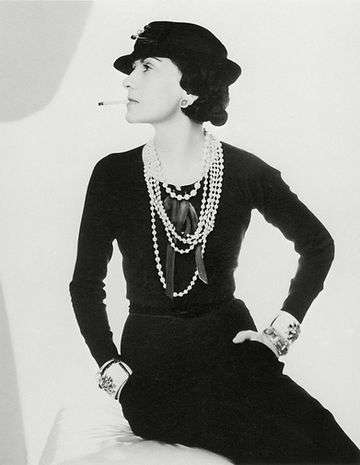

The Little Black Dress (LBD), a staple in every woman’s closet was first designed in the 1920s by Coco Chanel. It was designed during World War I, when the rules of the society dictated for women to wear black for 2 years after they widowed as “a sort of uniform for the woman of taste.” The graceful, versatile LBD design has evolved over the century but the fundamental framework of the design has remained the same. In the 1950s Hollywood used it to dress ‘femme fatale’ characters as the colour hinted danger. However, it was the iconic Audrey Hepburn in a LBD with pearls in the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) who made it indispensable. The LBD evolved from a neutral elegant dress to an evening cocktail dress, then to a symbol of a sexual woman and finally to the glamourous yet muted piece of clothing that it is today. With such a history, the dress carries a high Cultural Capital.

Photographer Cindy Sherman used this power of clothes along with wigs and props to create her seminal series ‘Untitled Film Stills’ (1977-1980). In the photos, she slips into a wide variety of roles that seem reflective of the day to day lives of women in the 70s, as portrayed in movies and the media. Her images bring to light stereotypes for women that are so deeply rooted in the society, constantly fed to us by mass media.

In the image Untitled Film Still #16, she is dressed in a LBD, with open-toed heels, an ashtray, and cigarette in hand. The image casts Sherman in the role of a ‘femme fatale’ and at the same time, she is reduced to nothing more than an object of desire. It is the dress that arbitrates between the viewing male subject and the mediated feminine subjectivity.

The images are pleasing to the male gaze and the women are preoccupied, pausing in mid-sentence, hesitating in mid-action, creating an intimate connection with the viewer. She presented a seemingly endless variation of female types, an innocent runaway, the voluptuous bombshell, bored housewife and adaptations of these identities so that there is something for everyone to relate to. Sherman explains the intentions of the images:

“People are going to look under the make-up and wigs for that common denominator, the recognizable. I’m trying to make other people recognise something of themselves rather than me.” -Cindy Sherman (1991)

Sherman’s images mock female stereotypes. They bring to light the subconscious messages a woman might be unaware of while dressing herself and the real capital value of clothes, while still being able to sense the “power” of the clothes. Cindy Sherman’s work is all ‘untitled,’ her images don’t declare themselves as being one or another. If in Untitled Film Still #16 she would be wearing a light coloured floral dress, she would appear more as a housewife smoking in her parlour rather than a femme fatale.

Are we all sheeple in the consumer matrix?

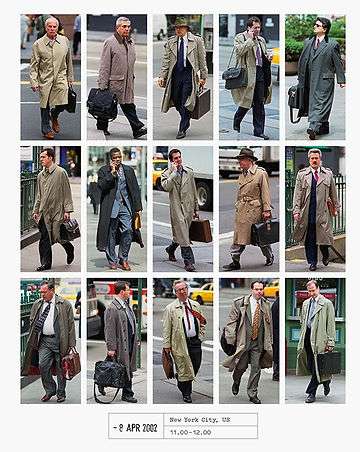

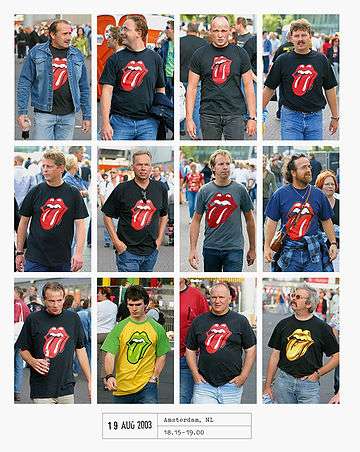

On the other end, there is photographer Hans Eijkelboom who started a photographic diary of strangers wearing the same or similar items of clothing. .” He arranges the similar images from his research into grids displaying how post-colonisation the exotic cultural differences have disappeared and has been replaced by global trends. His pictures capture similarities such as women clutching the same handbags, men wearing horizontally striped t-shirts, women wearing fur-lined parka hoods. Everyone in a grid seemingly embodies the same Cultural Capital.

People wearing the same colours, patterns, brands, or even supporting the same ideas (Rolling Stones or even Che Guevara t-shirts) through their clothes increase the cultural capital which in turn increases the cognitive power of the clothes. Fashion is based on collective acceptance about beauty. When one creates a new identity through clothes and inspires others to copy it, only then can it be considered fashion.

In the Photo Note shot on 8th April 2002 Eijkelboom photographed men in suits and trench coats marching to work. The men in the grid all wear muted coloured suits and ties, carrying a briefcase, all symbols reminiscent of the “Great American Dream” (Eijkelboom, 2015) and appear stereotypically masculine The trench coat is a sturdy item of clothing, the men in the photo look like they have stable jobs and a family.

The trench coat was developed during the First World War for the British Army, to be lightweight, waterproof and most importantly to be sturdy and long-lasting. The luxury clothing house Burberry is believed to be the creator of the trench coat, which means the coat carries a high embodied capital. The trench coat till date is a part of the army officer’s uniform. This gives the coat an institutionalised capital, giving it a respectable value. The suit is today a global uniform for the office going man. Paired with the trench coat and briefcase, every working man follows the respected and acceptable code.

Are we what we wear?

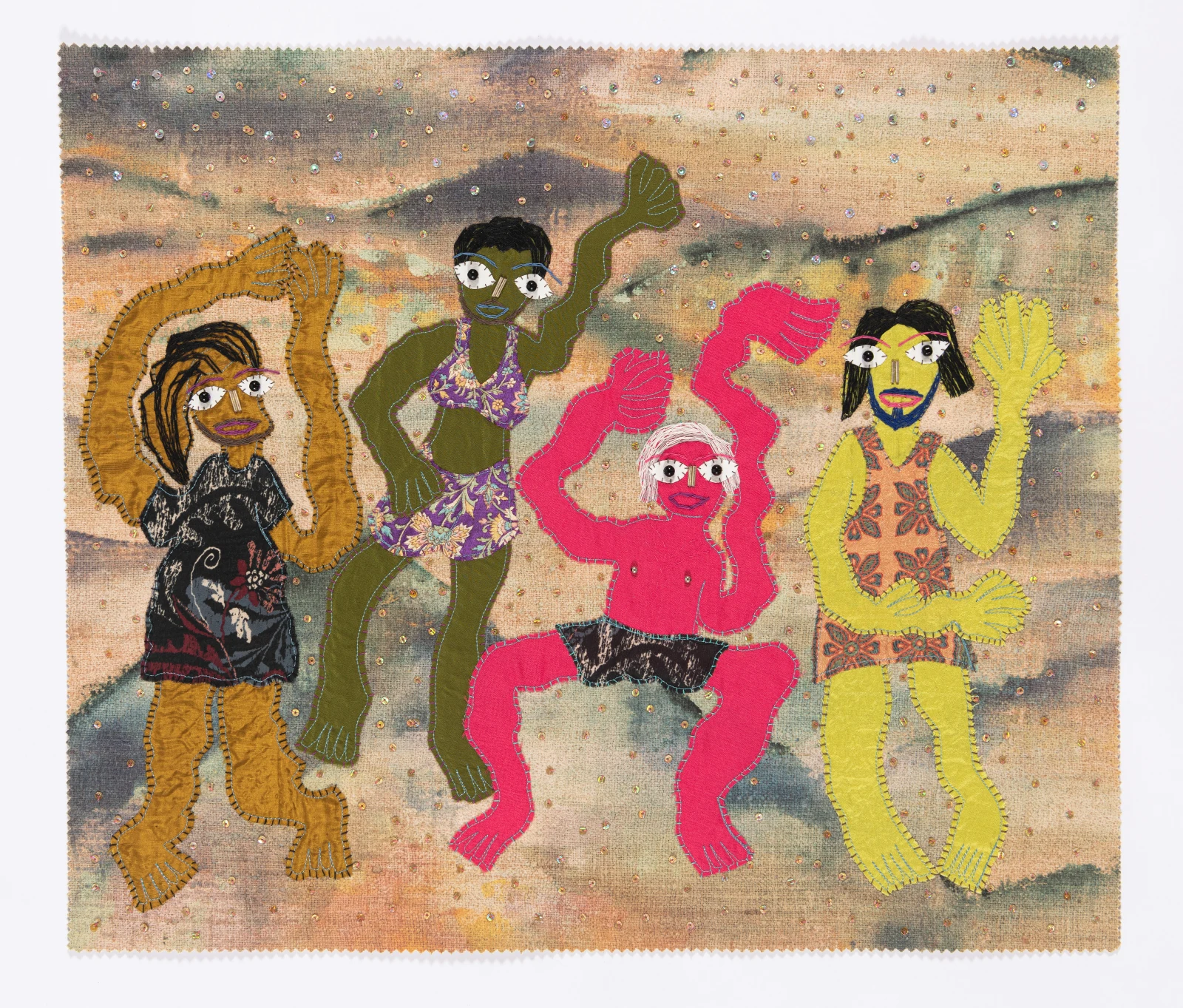

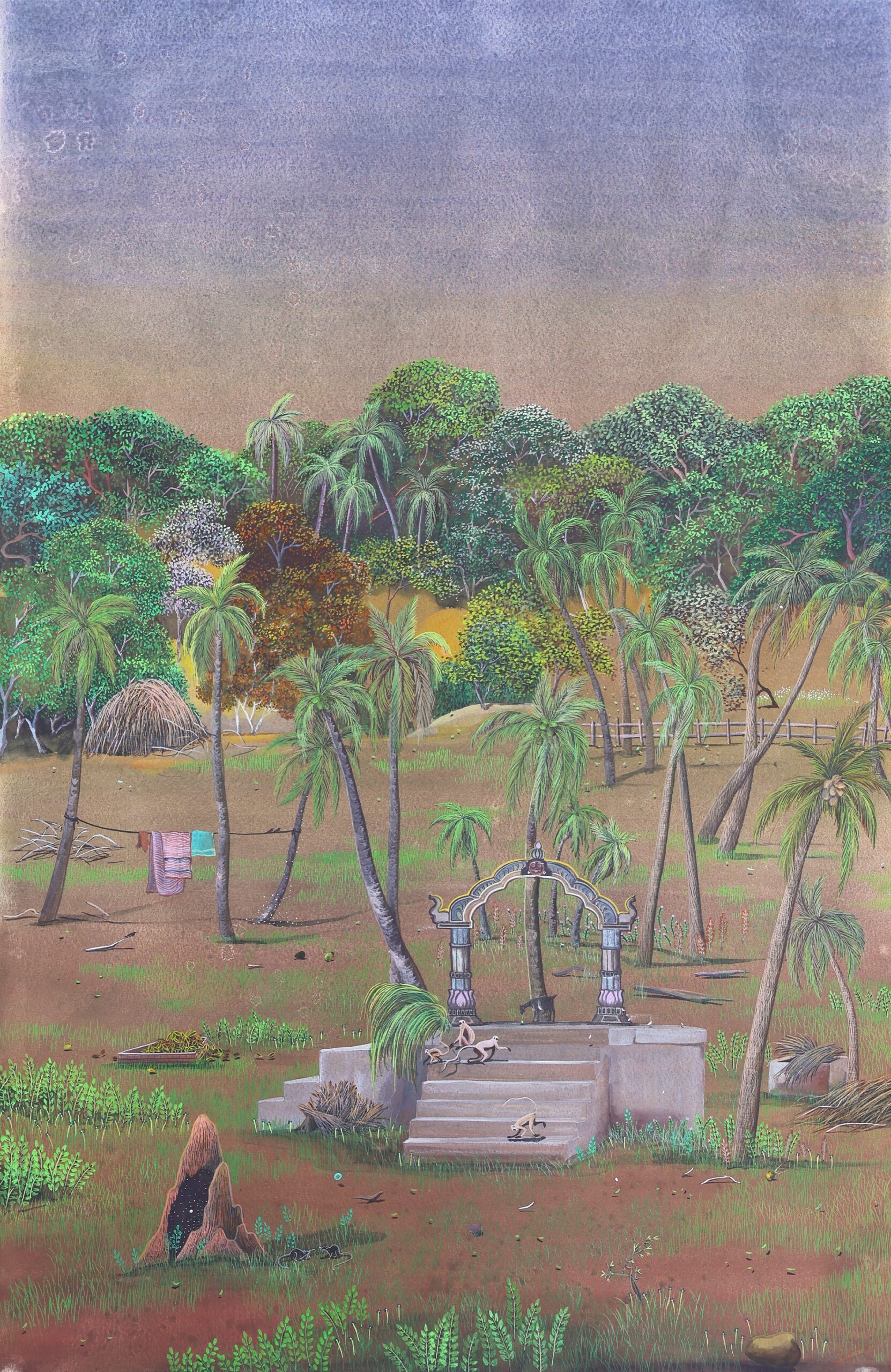

The body is a blank canvas and how we choose to present this canvas has an effect. When Eve took a bite of the apple from the tree of wisdom in the Garden of Eden she fashioned clothes out of leaves and twigs and covered her naked self. The physical reality of the naked human body was the first knowledge to enter human awareness. The feeling of shame and fear accompanied this awakening. In art, very often the body is not only the content of the work but also the canvas, frame, and medium.

In 1927, the author Mark Twain wrote that “clothes make the man, naked people have little or no influence on society” which means that people will judge you by the clothes you wear and without them, you will lose standing. Based on this statement the question arises that if people are to judge us by the clothes we wear, do our clothes serve as an armour against society? When are we ourselves, and who are we? Shakespeare said that “All the world’s a stage and men and women are merely players” so every day when we choose our outfit, we also choose what role we will be playing that day. Every morning when we stand in front of our closet, choosing what to wear, we are choosing what we want to say about ourselves to all those who see us that day. Cultural Capital affects our choices in ways we aren’t even aware of sometimes.

The exploration of clothing is important as it is concerned with both body and mind. By the virtue of choosing clothes in the morning, one can choose how compelling and memorable our performance is going to be. Artists have over the years have used the presence and absence of clothing to invite the viewers to feel a certain way when looking at the work. Inspiring admiration, lust, intrigue, loathing, fear, adoration are all examples of emotions that are very often induced using clothes as a tool.