The Stonewall Riots, which occurred at the end of June in 1969, is the mothership giving rise to June being recognised as Pride Month and several Pride events being held around the world to recognise the immense contributions of the LGBTQ community. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer individuals face steep challenges when it comes to navigating their lives without discrimination. Depending on where they are in the world, the punishment to live life on your own term ranges from passive aggressive obstacles at work to being stoned to death in countries like Brunei and Yemen.

Yet the world today is much more woke and open-minded than it once was. India overturned the colonial section 377 which penalised homosexuality. The USA, and most of Europe, has legalised same sex marriages. Queer culture is the most open and vibrant it’s ever been and the representation of non-heteronormative genders in pop culture are on the rise.

We rounded up three artists who were born way ahead of their time and paid the price for it. They constantly strove to maintain the balance between staying true to who they were and keeping their head low in order to survive. They teach us so much about making the most of this one precious life we have and how to hold onto our soul while conforming to the edicts of their time.

Lili Elbe

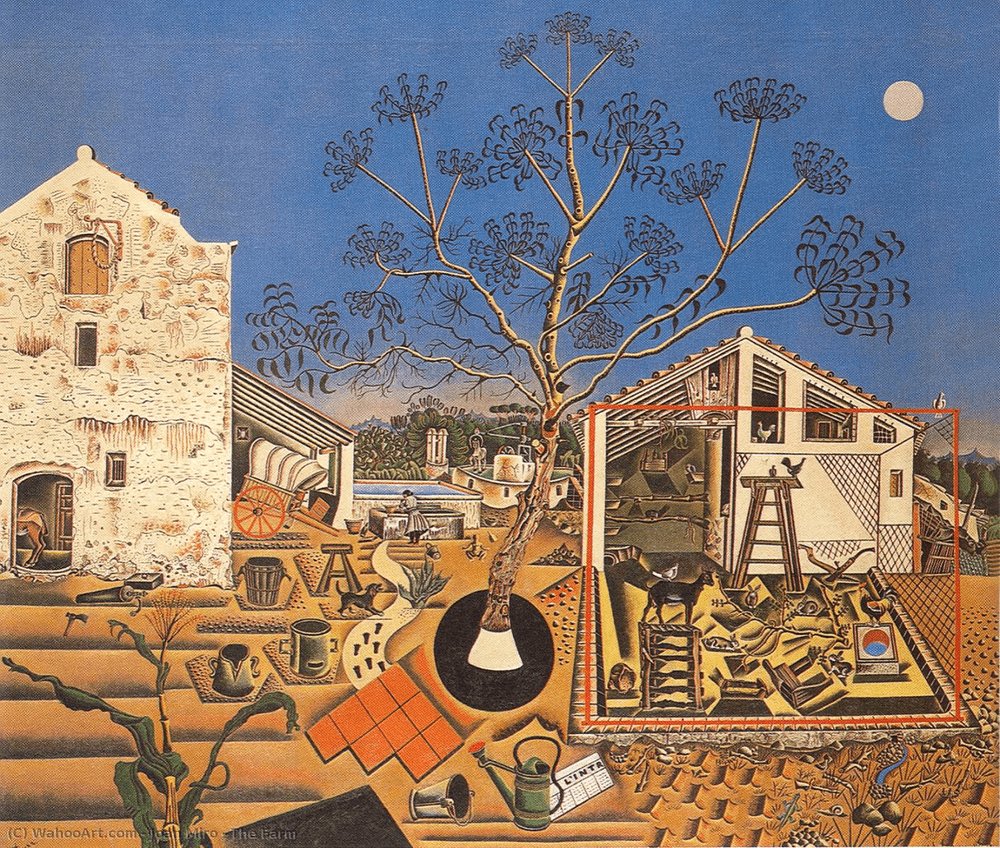

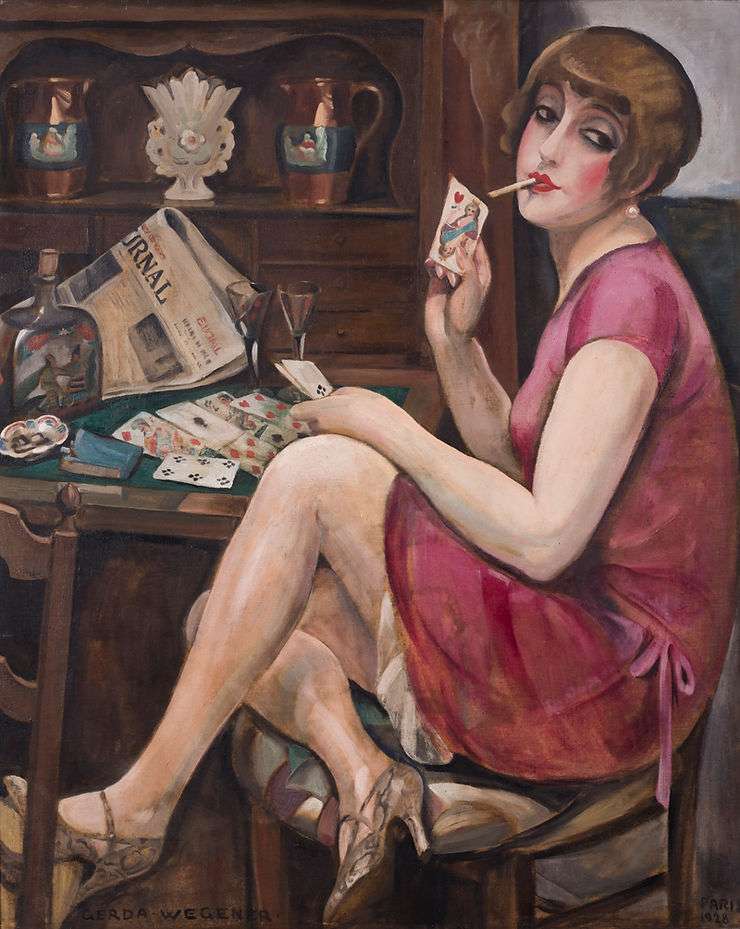

Sometime around 1908, Danish painter Gerda Gottlieb was in her studio at her flat, waiting for her friend Anna Larssen to show up. Anna was an actress who was to be the model for Gottlieb’s latest portrait. Anna called a few minutes later to say that she was stuck in rehearsals and wouldn’t be able to make it. She suggested Gerda use her slender-framed husband, Einar Wegener, as a stand-in for that day

Einar, a famed artist himself, agreed after some pleading. But as he put on a pair of stockings and heels, something began to change. A long-repressed part of him began to come to life. He said, “I liked the feel of soft women’s clothing. I felt very much at home in them from the first moment.”

After that day, posing for his wife in women’s clothes became a regular occurrence for him. The next two decades were a constant struggle to float the socially acceptable identity of Einar in public and be the feminine and flirty Lili in private – the person she felt she really was. The conflict of maintaining these two personas dismayed and dispirited him. It had taken Einar a long time to meet Lili. Now that he had discovered her, she was all he wanted to be.

When Gerda and Einar went to doctors with pleas for help, they diagnosed him as a degenerate. Others tried to have him committed in a straitjacket. To escape, the couple fled to Paris. Here Einar was retired permanently. Gerda introduced Lili as his sister. She began wearing women’s clothes, wigs and make-up full-time.

Lili did not paint. She had her own dreams and desires. Einar’s passions were not hers. She wrote in her diary, “It is not with my brain, not with my eyes, not with my hands that I want to be creative, but with my heart and with my blood.” She wanted to give birth to a child and hated living with a male physiology under her clothes.

Lili became so despondent that in 1930 she scheduled her suicide. May 1st was to be the ominous day. Then Magnus Hirschfeld came into her life. The sexologist was the first doctor to listen to her sorrows with empathy instead of judgement. A persecuted gay man himself, Magnus was trying to change how sexuality was viewed by society.

Magnus proposed a gender reassignment surgery on Lili while emphasising how new and dangerous this procedure was. She saw the surgery as a light at the end of the tunnel and didn’t care about the risks it posed. The initial series of operations were successful. But the fifth and final one, a womb transplant, was fatal. It would be five decades more before organ rejection preventing drugs would be introduced in the world. After a lifetime of fighting to be the person she wanted to be, Lili Elbe passed away in June 1931.

In 2000 writer David Ebershoff published the Danish Girl, a heavily fictionalised account of Lili’s life. The book was adapted into an Academy award winning movie starring Eddie Redmayne. But critics and loyalists note that both are a heavily sanitised and quite inaccurate portrayal of Lili’s life. For those interested, Lili left behind her story in her own words. Her memoir, titled ‘Man Into Woman,’ was published after her death in 1933.

Leonardo Da Vinci

If you’re having a hard time reconciling the Renaissance icon Leonardo Da Vinci as a queer figure, that’s probably because sex didn’t figure high on his list of priorities. He noted in his journal, “The act of procreation and anything that has any relation to it is so disgusting that human beings would soon die out if there were no pretty faces and sensuous dispositions.”

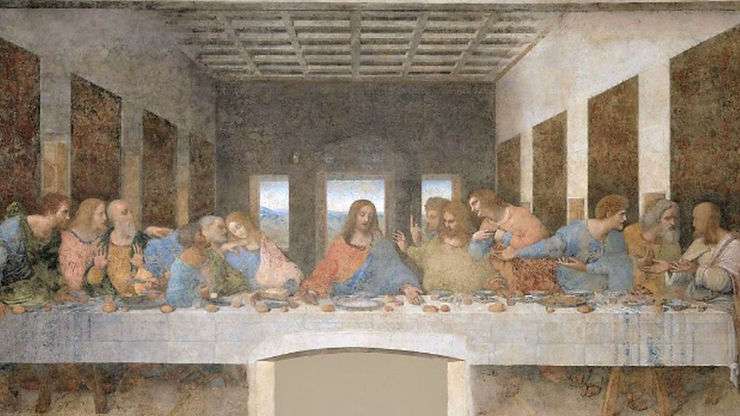

But many historians theorise that the reason behind his largely celibate existence was to keep his homosexuality repressed. Freud even published a paper in 1910 pondering the many ways why Da Vinci was certainly attracted to men. He was accused of sodomy, medieval speak for gay, in 1476 in Florence. The offence of sodomy carried the death penalty. He fled to Milan soon after where he gained patronage of the ruling Sforza family and set about creating one of his most famous works – The Last Supper. In her book, The History of Celibacy, writer Elizabeth Abbott suggests that it was the stress of the sodomy case that forced him into a self-imposed state of celibacy for the rest of his life.

For once upon a time, the young Leo did have a special gentleman friend or two. His one-time assistant cum boyfriend Salai was a great favourite of his. Salai even managed to insert a cheeky penis doodle in the great polymath’s notebook. In his book, Leonardo and The Last Supper, Ross King writes, “According to Lomazzo’s account, Leonardo’s passion for the beautiful Salai therefore reached its peak at about the time work began on The Last Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie.”

Michael White writes that he did find love in the arms of a young artist named Fioravante di Domenico in Leonardo: The First Scientist. The usually staid notebooks of Da Vinci even contain a passionate declaration to that effect: “Fioravante di Domenico at Florence is my most beloved friend, as though he were my …” A 19th century editor helpfully filled in ‘brother’ in the blank, hoping to eliminate the uncertainty. Somehow, we don’t think that’s the relationship Da Vinci had in mind.

Michelangelo Buonarotti

Every fifth grader knows the name of the man who painted the Sistine Chapel. But not everyone knows that said artist was gay. Or that he was gay right under the nose of the Vatican. Genevieve Carlton writes, “When he painted the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo used the muscular bodies of working Romans he met in the bathhouses as his models, transforming one of the holiest chapels in Catholicism into an altar to the male form.”

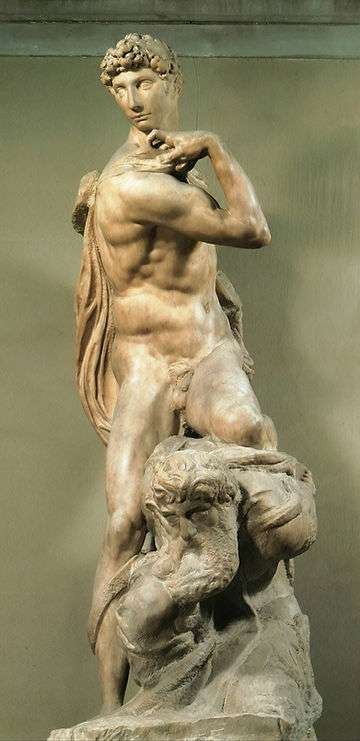

Michelangelo modelled his Genius of Victory sculpture on his lover Tommaso dei Cavelieri. He then created a sculpture of himself between the model’s legs. He wrote love poems full of homo-erotic references. When time came to publish them posthumously, his grand nephew Michelangelo the Younger changed all the masculine pronouns. Queer art historian John Addington Symonds made this startling discovery after being granted access to the Buonarotti family archives in 1863.

It’s hard not to descend into self-loathing when the propaganda of your time labels you a ‘degenerate,’ or vilifies you to be a sodomite. Or when your own family and friends think you’re unnatural. These great minds may never know that they were on the right side of history. But it’s their courage in embracing their full selves and in creating unforgettable art to channel their truth that we witness the full bloom of the human spirit.